The Voldemort Year

A special welcome to readers who are here by way of Becca Camacho’s lovely story about the farm in the Winter isssue of Edible Minnesota. It’s a magical way to drop the needle on Encore Farm’s 20th season.

Twenty years on seems like the right time to tell the story of Encore Farm’s first season.

For a long time, when asked how long the farm’s been around, I’d subtract a year. The Voldemort Year. The Year Which Must Not Be Named.

It was 2006, I was nearing the end of a 15-year career, but didn’t know it yet. I did know that the endless paperwork and pointless staff meetings made me look forward to being out with a migraine. The four-day weeks I shifted to after my dad died became permanent, and I began to spend my extra time interning on a nonprofit CSA farm. After two years, the farm staff invited me into their beginning farmer training program, which came with a parcel of land for my own use.

One fine summer morning I put on a cute tank top and overalls and drove to the farm. The fact that I even cared about appearances suggested that a bit more preparation was in order. Once there, I shouldered a one-row walk-behind seeder and bag of seeds, pausing in leisurely appreciation of the sunny 75-degree perfection of June.

I tucked seeds into straight rows, and carefully laid drip irrigation tape on top. Five days later, sprouts broke the surface. The once-brown expanse sported thin green lines. A week later, tiny beans were thriving. The summer was turning hot and dry, the way they like it. How lucky, I thought, to be a farming prodigy on the first try.

On the next visit, other green things had filled in between the seedlings, as well as in the paths between the rows. No problem. Two years of interning had taught, if nothing else, how to weed. So weed I did, navigating rows on hands and knees, yanking and pulling, enjoying the sight of a job well done.

Except the job didn’t stay done. An embarassment of weeds emerged through the summer. Dock and wild mustard followed redroot pigweed. Keeping up with them was impossible. In the time it took to clear two rows, more weeds sprouted where back at the beginning. Weeding is what you do when preventive cultivation fails. Cultivation is the gate that keeps things more or less under control and I’d let the gate fall off the hinges.

As the weeds grew as tall as the beans, then taller, time at the farm tapered, on the theory that if I couldn’t see how bad the situation was, I wouldn’t worry about it.

A call from the farm manager brought me back, when he promised to plow under the plot if the weeds went to seed, At three feet tall, the redroot pigweed easily dominated the crop, and resisted all attempts to grub it out. When I tried to kill it with a borrowed scythe, the blade bounced off the heavy stalks, leaving barely a nick. In a panic, I bought a 1970 Troy-Bilt rototiller, a $700 monster with blades conveniently located at the rear, for maximum access to feet and pants legs. My fear of the thing ensured very little weed destruction, which at that point resembled felling trees.

I was secretly relieved when the manager made good on his promise to plow under half the plot.

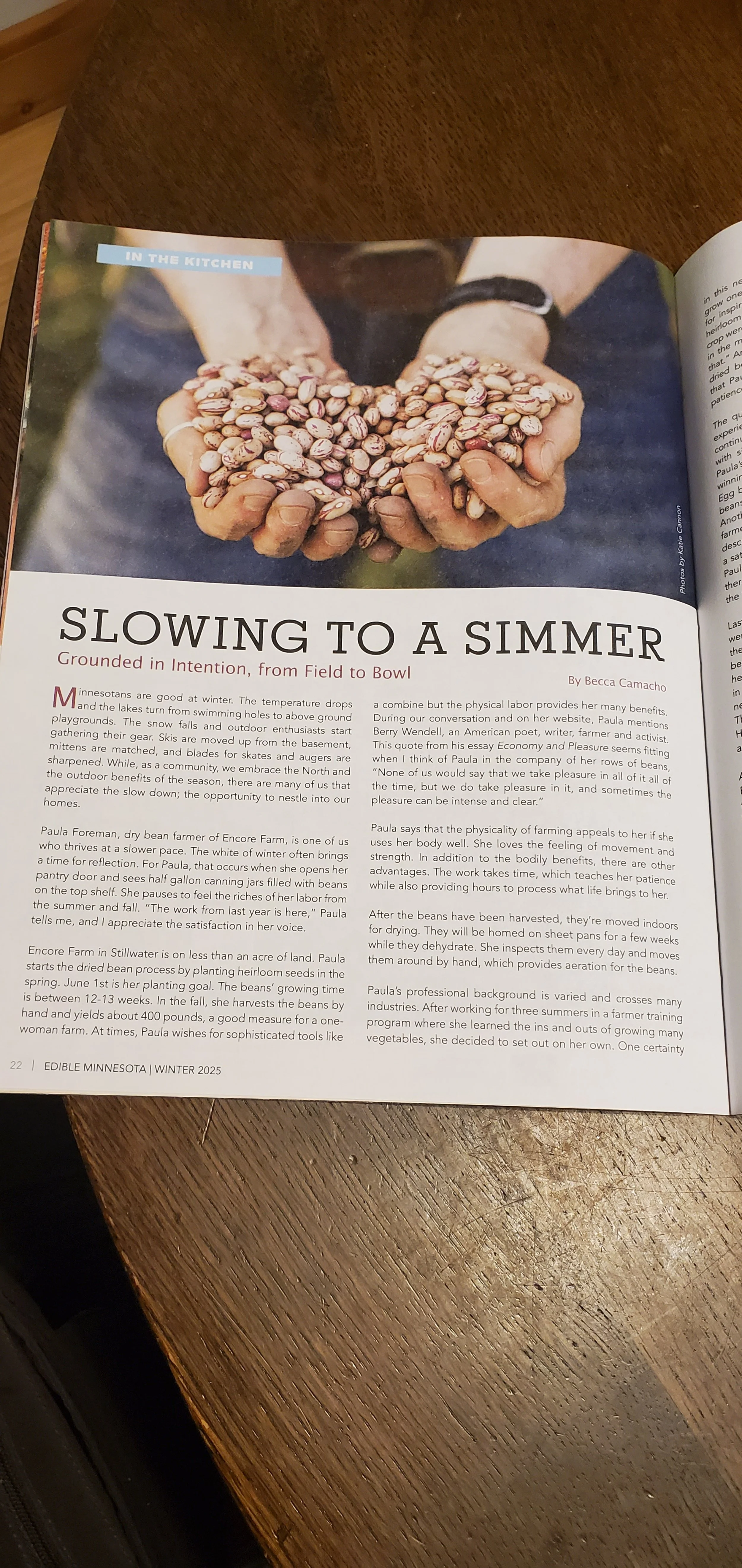

Twenty pounds of seed in the hands of a skilled grower could reasonably produce several hundred pounds of beans. The entire harvest, what I could find, filled a single quart canning jar.

***

This year’s plans call for five or six returning bean varieties, and another five, maybe six new ones. (These are the kinds of decisions that get made after an evening immersed in the farmer porn that is the Adaptive Seeds catalog. Spring is the season of high hopes.) And there will be a new Bean Zine. Could be some Encore Farm swag, too. It’ll be a big time.

Thanks for coming along.